How to Take Portraits in Photography (And Actually Make Them Good)

Let’s begin with a hard truth: Most portraits are bad. Not because they’re out of focus (though some are), or because they’re poorly lit (many are), or because the subject looks like they’re trying to hold in a sneeze. Most portraits are bad because they’re boring. They tell you nothing about the subject. They have no reason to exist except to technically qualify as a photograph of a person’s face.

And if you’re trying to become a portrait photographer—or at least a photographer capable of taking compelling portraits—you need to wrap your head around one central idea:

Portrait photography is less about the camera and more about the confrontation.

This is not a technical how-to. Or rather, it is, but it’s one where the technical stuff takes a backseat to what actually makes a portrait work. Anyone can learn how to set aperture and ISO. But creating a moment of connection between you and your subject, capturing something that wasn’t there the moment before the shutter clicked—that takes something more than gear knowledge and a light meter. It takes confrontation. Presence. Patience. Intuition. Curiosity.

Also, sometimes it takes a reflector and a softbox. So we’ll get to that, too.

Step 1: Learn to Look at a Face (And Really See It)

The first mistake new photographers make is trying to shoot a face the way they think a face should look. You know the ones. Chin tilted to the left. One shoulder raised. Side light. Vague smile. And while that may technically look good, it may also be the least interesting thing that person has to offer.

A good portrait doesn’t just show you what someone looks like. It reveals something about how they carry their history. It’s posture. Tension. Stillness. Eyes that are hiding something. Eyes that don’t hide anything at all.

So before you pick up the camera, take a second to actually look at the person in front of you. Where do they carry their energy? Do they sit rigidly upright, like they’ve spent 20 years in boardrooms? Do they slouch like a poet at a dive bar? Are they trying to please you? Avoid you? Dominate you?

Your job isn’t to tell them how to stand. It’s to figure out why they’re standing that way—and whether it’s worth capturing or correcting.

Step 2: Make It Personal (But Not Weird)

Portrait photography is, inherently, an invasive act. You’re putting someone under a lens and asking them to be honest. That’s a pretty big ask, especially when they’re wearing makeup and trying to forget the zit that’s blooming on their jaw and shaped like Montana but sized like China.

So, how do you get someone to trust you? Well, you talk to them. Like a human. You ask questions. You let them talk about themselves. You don’t treat them like a prop in your personal lighting experiment. This being said, you don’t sit down and do this for forty-five minutes. You can have a conversation with someone and put them at ease within a span of five.

The best portrait photographers are part psychologist, part stand-up comedian, part bouncer, and part therapist. Your job is to manage the emotional temperature of the room while simultaneously setting up the lighting and backdrop. You need to know when to back off and when to assert. When to let a moment land, and when to interrupt it with an inane sense of self-effacing stupidity that’ll cause your subject to relax and perhaps even laugh / chuckle / chortle.

This is where the real craft lives. Not in the settings, but in the sensitivity.

Step 3: Use the Light to Shape the Truth

Now let’s talk photography lighting. Because yes, it matters. And yes, it’s the difference between “this was taken in a DMV” and “this could hang in a gallery.”

There are a million lighting setups out there, but they all boil down to one question:

What are you trying to say about this person?

• Soft Light

Use soft light when you want something flattering, gentle, even. A large softbox, a window with sheer curtains, or open shade outdoors. This is what you use for beauty, for romance, for introspection. Soft light whispers.

• Hard Light

Use hard light when you want edge, intensity, definition. A bare bulb, direct sun, an unmodified speedlight. This is for drama. For portraits with tension. Hard light shouts. And sometimes it spits. Certain stocksused in film photography can be especially stylistic with hard lighting as their tonal range is more limited and makes for more contrast.

• Direction Matters

Front light flattens. Side light sculpts. Backlight isolates. Top light broods. Bottom light haunts. Every direction does something. Know what the direction means before you use it. Don’t just copy setups you saw on Instagram because “they look cool.”

Here’s a cheat code: Want the subject to feel grounded, human, and real? Shoot with soft side light. Want them to feel iconic, untouchable? Try a harder top light and step back.

Step 4: Posing Without Posing

One of the most paralyzing parts of portraiture—for both the subject and the photographer—is posing. Most people freeze the moment they hear “okay, just relax.” (Pro tip: never say that. It’s the fastest way to make someone not relax at all.)

Instead, think of posing as direction, not sculpture. You’re not arranging limbs. You’re giving prompts.

“Turn a little toward the light. Chin up slightly.”

“Sit how you normally sit when you’re waiting for someone.”

“Cross your arms if you want—but do it like you mean it.”

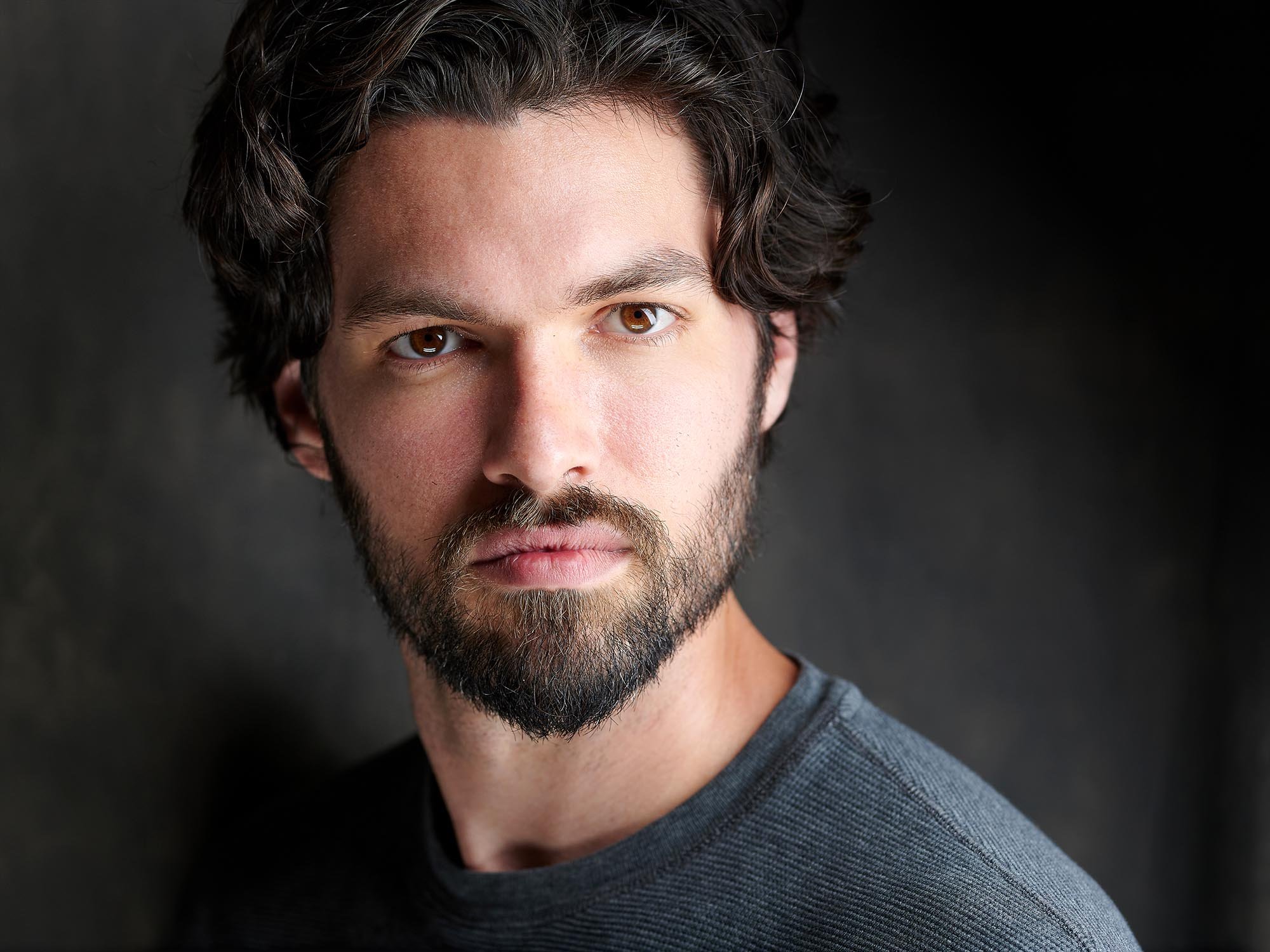

Honestly, I typically start off just having the subject square themselves with me completely and look at me straight-on and dead center. If the lighting is good and the photograph awesome, the subject will relax and you’ll have more leeway and room to maneuver with positions thereafter.

The more natural your subject’s pose, the more room there is for real expression. That said, not everyone knows how to look natural on camera. Some people need more structure than others. It’s your job to recognize that and adapt.

Let them move. Let them fall into themselves. The best portraits often come between the poses, when the subject thinks you’re adjusting a light.

Step 5: Choose the Right Lens (And Know What It Does to a Face)

Here’s where we get a little technical. Not because you should geek out over gear, but because the tools you choose literally shape the face in your frame. Whether professional or hobbyist photographer, the below are the most common focal lengths in portrait photography.

• 85mm: The Classic

Widely considered the perfect portrait lens. Why? Because it flatters the face. Compression keeps features proportional, and you can work at a respectful distance while still filling the frame.

• 50mm: Intimate and Flexible

A bit closer, a bit more environment. Good for editorial-style portraits where you want a sense of space.

• 35mm and Wider: Risky Business

Great for environmental portraits, but proceed with caution. The wider you go, the more distortion you introduce. Use wide lenses to say something about the person and their world—not just their bone structure. If you’re using a 35mm lens, you’ll be doing a full-length portrait with room to spare around the subject.

• Longer than 85mm?

Absolutely—135mm is gorgeous for ultra-compressed, creamy-background headshots. But know that the longer the lens, the further away you have to stand. This is absolutely fine if you have the space, but for corporate headshots taken place on-site and in an office, for instance, this can be limiting.

Step 6: Get the Technical Stuff Right, Then Forget It

Yes, your aperture matters. Yes, you should understand depth of field. Yes, you should know how to expose for skin tones.

But once you’ve nailed the photography basics—ISO low, shutter fast enough, aperture depending on the look you want—stop fiddling with the camera.

Your subject can tell when you’re more in love with your settings than with them. And a portrait is always, first and foremost, about them.

Here’s what I recommend:

Set your exposure. Lock it in.

Test your light. Adjust if needed.

Then let the interaction take over.

Shoot enough frames that you catch real transitions—those moments when the face softens, or tightens, or turns inward, or lights up.

Step 7: Retouch with Respect

A portrait isn’t a glamorized fiction. It’s an interpretation of a real person. And post-production should honor that.

Yes, clean up blemishes. Yes, balance skin tone. Yes, remove that weird glare that makes it look like their forehead is hosting a revival tent. But do not erase the lines that show they’ve lived.

Freckles aren’t flaws. Neither are laugh lines. If you’re retouching someone into anonymity, you’re not a photographer—you’re a witness protection officer.

Your edits should whisper, not shout. Touch lightly. Or, better yet, learn to light better so you don’t have to fix everything in post.

Step 8: Know What You're Really Doing Here

At the end of the day, portrait photography, whether it be a corporate headshot done in a midtown high-rise or a series of family photos at a birthday party is about presence. It’s about giving someone the rare gift of being seen. Most people go through life never really being looked at—at least not without judgment or agenda.

A good portrait says, “I saw you.” A great one says, “And I saw something you didn’t know was there.”

That kind of seeing doesn’t happen on autopilot. It doesn’t happen when you’re obsessing over sharpness or overthinking hand placement. It happens when you’re locked in. When you’re present. When you’re patient enough to wait for the moment and quick enough to capture it when it shows up uninvited.

Final Thought: Stop Trying to Make Pretty Pictures

A pretty portrait isn’t the goal. A true one is.

Beauty in portraiture isn’t about symmetry or flawless skin or perfectly curled hair. It’s about truth. And truth, when lit with the right light and captured in the right moment, is the most arresting thing in the world.

So go out there. Take a hundred portraits. Take a thousand. Most of them will be bad. A few will be good. And once in a while, you’ll make one that makes you stop in your tracks and think:

That’s it. That’s who they are.

And when that happens, you'll know you're not just taking pictures anymore. You're making portraits.